The Western Polemic is a reader-supported publication. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber or making a one-time or recurring donation to show your support. For more information read Introducing the Western Polemic.

The work on this series which explores the history of Western education began in the summer of 2024, back when the Western Polemic was just a pipe dream. Much has been discovered during that time. Many secondary sources dealing with the dynamic world of the ancient Near East have been examined in an attempt to locate the points of cultural exchange between Greek civilization — the foundational civilization of the Western world — and the much older civilizations to the East.

We were gripped by many questions. Which aspects of cultural and intellectual achievements were universal to mankind, and in the case of the Greeks, which were borrowed from the older cultures of the Fertile Crescent? And, which were the isolated products of Greek genius?

In this essay series, Scott Miller and I seek answers to these questions and many more concerning the very earliest developments of the Western intellectual tradition. We also inquire, perhaps most importantly, on the means by which it transmitted to modern generations: education.

The unprecedented “Greek Miracle” greatly inspired the Romans and will forever be the cornerstone of our illustrious Western knowledge production tradition. Please join us on our inquiry into the history of Western education as we begin by tracing both the universal and unique cultural features of the Greeks.

A History of Western Education - Part One: From Orient to Occident

By James Pew and Scott Miller

Introduction

In contending with the history of Western thought, we could do no better than to start with Aristotle’s dictum from his work on politics which reads “as in other matters, so also in politics, it is by considering the growth of things from their beginning that one obtains the clearest understanding of them.”1 Many ideas have histories that stretch far back into antiquity. The present authors are continually returning to that time, seeking answers to something of relevance today. It doesn’t take long for one to discover, when examining this critical period, that cultural development in antiquity was influenced by the earliest known human civilizations, and the earliest known civilizations were influenced by events that occurred further back in prehistory. Because of this, it is very easy to extend one's thinking (and expository writing) all the way down to the dawn of man, or, at least to the time of the Neolithic Revolution (12000 BCE), when agriculture and the first divisions of labour began to take shape. While it might be admitted that most of the time this level of backstory is unnecessary, there are those subjects which provoke such unbridled curiosity, they leave one with no choice other than to ask questions, and seek explanations, concerning the very earliest happenings. This essay series which we embark on today will not include the more than one hundred thousand years of development of early modern humans. Instead, it begins roughly around 5,000 years ago, when civilizations first produced writing (a crucial prerequisite for education).

Our main theme for the series is the Western intellectual tradition, a tradition of knowledge production and education. The emphasis is on how we both produce and transmit knowledge (and ideas). Our method is very much in the spirit of Arthur Lovejoy’s history of ideas scholarship, modified in several ways by our own unique approach. Early in this series, we will attempt to detail the inception of informal, then later organized education, as a concept, and detail its origins and influence in the Western world. We say “attempt,” because among leading scholars there is much debate over the connections of older civilizations in neighbouring regions to the early Bronze age Greeks. And of the early Bronze age Greeks with the late Bronze age and Iron age Greeks. And the subsequent influence they may have had on the later Archaic Period Greeks who developed the foundation of the Western intellectual tradition.

From Orient to Occident — Greece as recipient of knowledge from the more ancient East

In the 19th century, three new discoveries began to militate against “the image of pure, self-contained Hellenism.” They were: “the reemergence of the ancient Near East and Egypt through the decipherment of cuneiform and hieroglyphic writing, the unearthing of Mycenaean civilization, and the recognition of an Orientalizing phase in the development of archaic Greek art.”2

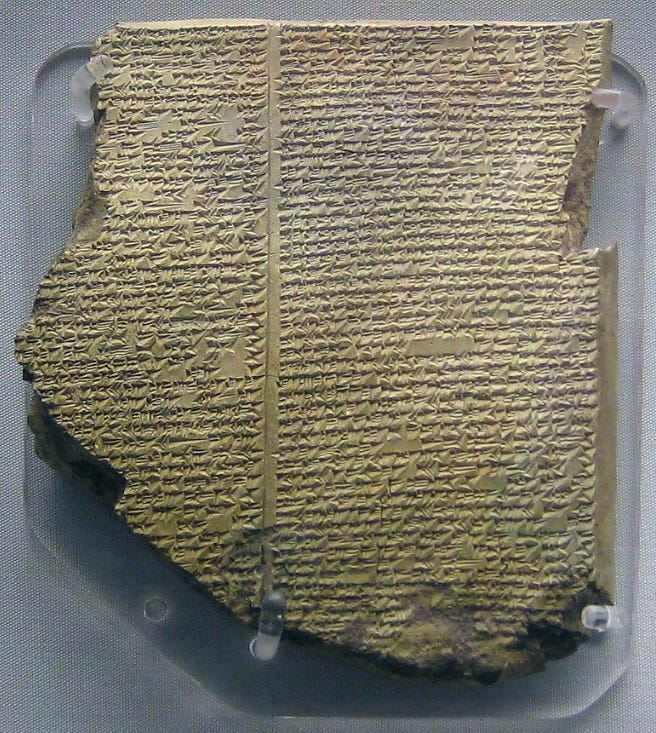

To sketch the significance of just one of these discoveries, what the discovery of cuneiform writing means for the history of writing and literature, we have with cuneiform not only the first writing system in human history, but also the longest running (it was in use for over 3,000 years); cuneiform texts are, at the same time, the best preserved and most numerous textual records from the ancient world by far (there are hundreds of thousands of cuneiform documents in museum archives today because the signs were inscribed on clay tablets which preserve better across time than other materials used for writing in ancient times). This complex writing system, consisting of thousands of signs, was developed first in Mesopotamia by the Sumerians and, subsequently, it was adopted by the Akkadians, Babylonians and Assyrians in the same area. It emerged c. 3200 B.C. as a response to social and economic complexities generated by the world’s first cities: invariably, the impetus to create a writing system comes down to the need to document and track the transfer of food stuffs, material goods, temple offerings, and so forth, the administration of complex urban society. On the other hand, written literature in the form of myth, poetry and the like, are secondary developments that may follow a long time later (if at all). In centuries to follow, Mesopotamian scribes would begin to write down epic tales telling the exploits of heroic kings, such as Gilgamesh, along with hymns and prayers to the Mesopotamia gods, incantations to ward off demons and diseases, texts containing lists of known phenomena, proverbs, reports of astrological phenomena and their omens, medical and magical texts to be used by the healing expert, and many text types besides.

On the Question of Greek Borrowing from the more ancient East: This series will delve into the work of many of these cutting-edge historical scholars who follow the evidence from Orient to Occident. Academic’s like Albin Lesky, M.L. West, Walter Burkert, Margalit Finkelberg, Harald Haarmann, Daniel Ogden, Mark Griffith, and more.

It is no easy task to establish links between Greece and ancient Near Eastern civilizations, and the difficulty has to do with more than vast expanses of time and space. Typically, modern scholars of classical Greece have a tendency to “transform ‘oriental’ and ‘occidental’ into a polarity, implying antithesis and conflict.” According to Burkert, it was not until the Greeks fought back the Persian Empire that they became aware of their distinct identity (as separate from the orient). In addition, it was not until many years later, during the crusades, that “the concept and the term ‘Orient’ actually enter(ed) the languages of the West.”3 The reluctance on the part of many scholars to accept a universal conception of cultural development which involved “borrowing,” “loan words,” and “cultural diffusion” amongst the different ancient peoples living in both the Near East and the Aegean regions, is due to intellectual currents that first took shape in Germany over two centuries ago. In Burkert’s words, “Increasing specialization of scholarship converged with ideological protectionism, and both constructed an image of a pure, classical Greece in splendid isolation.”4

It was essentially a trio of academic fads that “erected their own boundaries and collectively fractured the Orient-Greece axis.”5 The first was the breaking apart of theology and philology. Until well into the 18th century, “the Hebrew Bible naturally stood next to the Greek classics, and the existence of cross-connections did not present any problems.” The second was the rise of the ideology of Romantic Nationalism, “which held literature and spiritual culture to be intimately connected with an individual people, tribe, or race. Origins and organic development rather than reciprocal cultural influences became the key to understanding.”6 And the third was the discovery by linguistic scholars of “Indo-European,” the “common archetype” of most European languages (as well as Persian and Sanskrit).7

Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff offered a “scornful assessment” indicative of the faddish and far more isolated conception of ancient Greece in 1884: "the peoples and states of the Semites and the Egyptians which had been decaying for centuries and which, in spite of the antiquity of their culture, were unable to contribute anything to the Hellenes [the Greeks] other than a few manual skills, costumes, and implements of bad taste, antiquated ornaments, repulsive fetishes for even more repulsive fake divinities…”8 A common take at the time which would later prove to be quite incomplete. It should be noted that Romantic Nationalism, coupled with the discovery of Indo-European (which demonstrates no link between European and Semitic languages) seems to have contributed to what gave “anti-Semitism a chance.”9 Tragically, it was at the point when the Jews were finally being granted full legal equality in Europe when national-romantic consciousness and the rejection of orientalism helped set the stage for the escalation in Jewish persecution that eventually led to the horror of horrors: the Holocaust.

The Mesopotamians would never, as the later Greeks did c. 600 B.C., formulate an abstract concept of “nature” and analyze phenomena as having a natural developmental explanation rather than the traditional explanation (that being, e.g. the gods made it so). Thus, they would never develop philosophy or science as we think of it, and so there are certain categories of analysis and knowledge that are uniquely Greek in the ancient world. However, as the innovators of a form of agrarian society that was productive and sophisticated enough to sustain the world’s first cities, Mesopotamians needed to be able to examine and quantify time (in order to know when to plant) and so they developed the lunar calendar of 12 months, they developed the 12 double-hour day, they gave names to the observable planets and charted the night sky into constellations;10 They needed to be able to measure physical space and allot pieces of land to land owners, and so they created the world’s earliest form of basic geometry.11 The types of knowledge just named are the types of knowledge that scholars believe would have been of interest to the Greeks, and, indeed, many suspect that iron age Greeks borrowed these insights from the Babylonians. Whether the Greek story of Heracles could have been influenced by Mesopotamian hero epics such as the Epic of Gilgamesh is a more contentious —though intriguing— topic.

So, how did Greece find itself in a position to receive the baton of civilization and even to carry it further forward? Because of the great work of modern scholars, we know that an informal but early (proto) archetypal version of education (not yet organized education) begins in the Mediterranean, in archaic Greece, before the classical period. Even before this, although it is not exactly clear as to the extent, it has been determined that Bronze Age Greek cultures located around the area of the Aegean sea (also known as Aegean Civilization) – the Mycenaean on mainland Greece, the Minoan on the island of Crete and the Cyclades (also known as the Aegean Islands) – were not only in contact with each other, but also with neighboring civilizations: Egypt, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor, and the Levant.

According to British philologist M.L. West, in his highly significant 1997 volume, The East Face of the Helicon, “...although [ancient Near Eastern] culture is far from being unitary, it is characterized by such far-reaching supra-regional interrelationships that one cannot treat the countries in question in isolation.”12 As West observes, “for some six thousand years, from the seventh millennium BC to the first, a steady succession of arts, crafts, and comforts found their way from south-western Asia, the cradle of the Neolithic revolution, to south-eastern Europe and to that gnarled outpost of Europe that we call Greece”. There is no better example of a technology that transmitted from Orient to Occident than the technology of the written word itself, and, as pointed out in a review of The East Face of the Helicon, “Akkadian cuneiform side by side with Aramaic, Phoenician, and Greek alphabetic script produces a continuum of written culture in the eighth century which stretches from the Euphrates to Italy.”13

However, West postulates that the influence Egypt had on Greek myth and poetry was “vanishingly small.”14 Because of this, West compares what is known about ancient Near Eastern culture (using Mesopotamian, Anatolian, Syrian, and biblical sources)15 with the early Greeks in order to trace its influence on Greek poetry and myth, “which may be presumed to have been narrated in early poetry,” and which found its way to the Greeks through “cultural diffusion.”16 However, West does provide, in the first chapter, an overview of the influence of the Near East (including Egypt) on Greek culture for basic agricultural and civilizational developments such as the ability to measure time and space and to record data with a system of writing. The oldest materials that Martin West uses in his Greek poetry and myth comparative analysis with the ancient Near East are Mesopotamian. Some of these written artifacts stretch back to the third millennium B.C. But he also uses a variety of ancient Near East materials that fill the chronological gap between the ancient Mesopotamians and Homer. Most of these texts were written in Greek, Hittite, Akkadian, Ugaritic, Phoenician, Aramaic, and Hebrew.

Greece — the transmission of knowledge from early to late Greek civilization

For our purposes, the biggest questions concerning these ancient periods are fundamental: How much cultural contact was there between neighbours like the much older Mesopotamians and the early Greeks (Mycenaean-Minoan-Cycladic), and how much of it transmitted to the Archaic Greeks (800 – 450 BCE) who so influenced the Classical Greeks (490 – 323 BCE), the Hellenistic Greeks (323 – 31 BCE), the Romans and everyone else who followed? As Berkeley professor of Classics Mark Griffith wrote, “...it would surely be a mistake to attempt any comprehensive account of early ‘Greek’ education without considering the practices of their predecessors and neighbors,” and even though the investigation “must necessarily be speculative and/or lacunose,” it “nonetheless seems relevant and worthwhile.”17

A complicating factor in assessing the transmission of knowledge from early to later Greek civilization is certainly the Bronze Age collapse. The Bronze Age Collapse (a period between 1250 and 1150 BCE) was an event, or more likely, a series of events that greatly affected the major Mediterranean civilizations at the time. Archaeologists have debated this calamitous period for over a hundred years. Many plausible theories have been put forward. Some posit the devastation was caused by natural catastrophes (earthquakes), others say drought and famine brought on by climate change, and other factors like internal wars, disruptions of trade relations, and invasions by outsiders (including the mysterious Sea Peoples), all put forward as plausible explanations for the Bronze Age Collapse. Scholars like Eric H. Cline think it must have been the accumulation in quick succession of all or many of the troubles previously listed that ultimately caused the collapse. According to Cline:

“Perhaps the inhabitants could have survived one disaster, such as an earthquake or a drought, but they could not survive the combined effects of drought, famine, invaders, and earthquakes all occurring in rapid succession. A domino effect then ensued, in which the disintegration of one civilization led to the fall of the others.”18

By 1200 BCE the majority of the sites on Crete were abandoned, and evidence for administrative organization and links with other cultures disappeared. By 1100 BCE there is little archaeological evidence for the Mycenaeans, and archaeological evidence suggests that a new population of Greeks speaking the Dorian dialect had pushed south through mainland Greece, conquering the Mycenaean centers as they went, destroying the palaces and palace economies in the process. The collapse of Mycenean palace economy meant that there was no longer a purpose for the linear B writing system that had been imported from the Minoans — notably, this writing system had only ever been used by Bronze age Greeks for the purposes of tallying objects so the information was purely economic in character (although occasional mentions of goods for the religious rites of gods such as Zeus show that the Mycenaeans shared some common religious views with later Greeks).

After the Bronze Age Collapse, Greece entered a dark age: not only had Greek palaces collapsed, but kingship itself ceased as an institution in this time. Greece in the early first millennium B.C. was governed by warrior chiefs who made policy in coordination with assemblies of male warriors (ergo, primitive democracy). In addition to new stimulus from the Orient (for example, the Greek adaptation of the Phoenician alphabet c. 800 B.C.), Greece would in due course respond to its dark age setbacks by innovating sophisticated legal codes, city-states with proto-modern civic structure, the world’s first democratically predicated modes of governance, and intellectual and artistic feats which are irreducibly attributable to the genius of Greek innovation.

Future installments will offer more details on what is known about the cultural diffusion that took place in the ancient world, between ancient Near Eastern civilizations and the proto-Greeks. We will once again dip into M.L. West’s excellent The East Face of the Helicon, and other informative volumes like The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age by Walter Burkert. Stay tuned.

Bibliography

Boas, George. 1966. Essays on Primitivism and Related Ideas in the Middle Ages. New York: Octagon Books, Inc.

Powell, Barry. 2000. “The East Face of Helicon. West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry.” Bryn Mawr Classical Review, May 8, 2000. https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2000/2000.05.08/.

Burkert, Walter. 1992. The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

West, Martin L. 1997. The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Cline, Eric H. 2021. 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed (Revised and Updated). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Griffith, Mark. 2015. “Origins and Relations to the Near East.” In A Companion to Ancient Education, edited by W. Martin Bloomer, 7–25. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Thanks for reading.

Or, make a one-time or recuring donation here.

Boas 1966. 174.

Burkert 1992, 3.

Burkert 1992, 1.

Burkert 1992, 1.

Burkert 1992, 2.

Burkert 1992, 2

Burkert 1992, 2

Burkert 1992, 2

Burkert 1992, 2

West 1997, 28.

For a quick initiation into Babylonian geometry, see:

West 1997, viii.

Powell 2000.

West 1997, vii.

West 1997, vii.

West 1997, vii.

Griffith 2015, 8.

Cline 2021, 173.

Excellent! I hope they still teach this in schools? I remember more than 30 years ago, as a young back packer, trudging from city to city in Europe with little money, staying in hostels, but always going to as many museums and art galleries as possible in each location. "Those who don't know history, ..." You don't know what you have, until it's gone.